Shropshire holds a special place in my heart, and I have been fortunate enough to spend a lot of time there over the last few years. I have been bowled over by just how many big, old trees there are, standing sentinel amongst the rolling fields and rich hedgerows of this idyllic county. Ranging from the uplands of the Shropshire Hills National Landscape to the fertile North Shropshire Plains, Shropshire’s hedgerows and hedgerow trees are a special, and essential, aspect of a landscape celebrated for its beauty, fascinating geology, and for being the birthplace of arguably the most famous naturalist in history, Charles Darwin.

Hedgerow trees are simply trees within a hedgerow left to grow into their natural size and shape, rising above the hedgerow line. They provide huge benefits to our wildlife, our environment and to us as humans. About this time last year, I wrote a Tree Talk piece looking at the problems our hedgerow trees face nationally. To say, ‘they’re not getting any younger’, would be an understatement. They are old and only getting older. You can read the full article here.

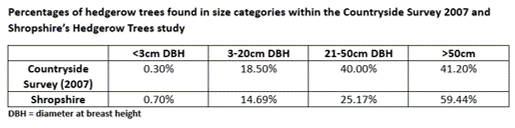

In that post, I outlined how our national hedgerow litmus test, the Countryside Survey, has shown that most of our hedgerow trees are quite big (old), and very few are small (young). Why is this a problem? It is now thought that, nationally, the recruitment of young trees is insufficient to meet the mortality of our older hedgerow trees, which will gradually die out over the next few hundred years without being replaced.

National data is super important. It is fantastic news that the update to the Countryside Survey by UKCEH is currently underway. However, I believe local data is essential to feed more area-based decision making to inform Local Authority level strategy, landscape-level plans, and community action.

Last year, for my MSc research project, I undertook a hedgerow tree population analysis of agricultural land in Shropshire, to feed back to Shropshire County Council and (hopefully) impact local hedgerow conservation efforts across the county.

Using a combination of Defra’s Hedgerow Survey Handbook and the People’s Trust for Endangered Species’ (PTES) Great British Hedgerow Survey methodologies, I carried out a standardised, randomised survey of 72 hedgerows across the county, totalling over 12km in length, and including 181 hedgerow trees.

Hedgerow trees in Shropshire were found to be even more weighted to large trees (and therefore likely older trees) compared to the most recent Countryside Survey, in 2007. This demonstrates a significantly ageing hedgerow tree population and adds weight to the case for initiatives to boost younger trees in our hedgerows.

Countryside Survey data found ash to be the most common hedgerow tree in Britain with oak in close second, making up over 65% of the population across a fairly even split. In Shropshire, the population was weighted very heavily towards oak, making up 50.35% alone. There was a marked lack of ash, only making up 10.49%. This did not appear to be a result of death or removal due to ash dieback, the signs of which would likely remain. We could perhaps attribute it to local growing conditions, sampling limitations, or an overall favouring of oak as the principal hedgerow tree species.

The lack of ash in Shropshire’s hedgerows at least means that they cannot be affected by ash dieback, however the dominance of oak is a real risk, with conditions such as acute oak decline increasing in prevalence. The old case of not putting all your eggs in one basket definitely applies here.

The lack of diversity in Shropshire’s hedgerow tree species highlights the need for marked efforts to increase the range of tree species. In an urban setting, the 10-20-30 rule of planting no more than 10% of one species, 20% of one genus and 30% of one family has been used, adapted, and critiqued throughout the years. This could provide a good, strategic baseline for planning hedgerow tree biodiversity improvements, although ecological, environmental, landscape, and social factors must all be considered when choosing appropriate species.

In my research, more than 60% of hedgerow trees were found to have machinery damage. In most cases this was not serious damage, but any breaking of the bark and exposure of sapwood brings with it the threat of infection, and potentially a reduction of lifespan. Fungal communities in old trees, however, are essential for a huge array of wildlife (see our deadwood Tree Talk here) and many tree managers now actively veteranise trees to promote deadwood. In order to delve further into the health of Shropshire’s hedgerow trees, a summer condition assessment would be really useful - something I was unable to do during the winter months.

More than 90% of hedgerows surveyed in my research were flailed - this could be one of the reasons for the low recruitment of young hedgerow trees. However, with so people managing their hedges in the same way, there is an opportunity for widespread change by adapting flailing methods to focus on identifying and retaining hedgerow trees.

Two of the landowners in my study suggested that both landowners and agricultural contractors would benefit from improved education on the advantages of hedgerows and hedgerow trees, alongside enhanced management practice. This could entail leaving young hedgerow trees to grow, or planting new ones and finding ways to bring them back into farming systems.

Encouragingly, over half of landowners who were questioned said there should be more hedgerow trees, and nobody said there should be fewer, with greater incentives and education being mentioned as the best avenue to boost the hedgerow tree population.

I think the introduction of a graded incentive system, alongside better education, could provide a real boost here, with retention of the smaller size categories of trees (which are currently missing), and the larger sized trees (which are the most ecologically and environmentally important) being more incentivised. This could promote the recruitment of young trees to maturity over a long period of time, whilst showing appreciation for their elder cousins.

Historically used for firewood, timber, and tree products (such as tree-fodder for animals), hedgerow trees were once essential parts of farming systems. However, for the future of hedgerow trees, I believe we need to focus on exploring novel ways of incorporating them back into farming systems to make them as desirable as possible for land managers.

As farmers are already incredibly hard pressed to deliver cost-effective food production, finding ways that trees can provide both public benefits and a revenue stream for farmers is essential. A current trend towards agro-forestry is exciting for hedgerow trees, alongside new options available as part of the new Environmental Land Management schemes.

It is not just down to farmers and regulatory bodies to sort this problem out. It is going to take the collaboration of all sectors to achieve the change we need by sharing funding streams, knowledge, resources, and skills.

Within Shropshire, I am looking forward to discussing my findings with Shropshire County Council and local land managers to explore how we could improve the scenario for Shropshire’s hedgerow trees going forward.

My full report is available on request. Please get in touch with me on will.fitzpatrick@treecouncil.org.uk for more information.

Will Fitzpatrick is The Tree Council’s Community Engagement Officer, with a particular focus on hedgerows.

MORE: Our landscapes could be transformed by approaching gap in hedgerow tree succession